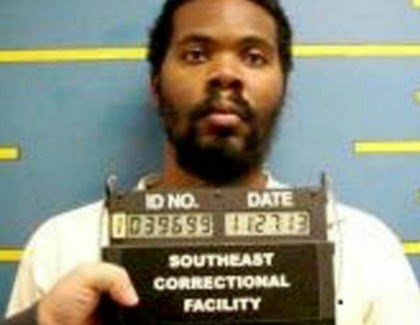

I want to weave a braid of the story of Cornealious (Mike) Anderson, the

philosophy of Thomas Hobbes, and this week’s parashah, Bechukkotai.

There are some heavy-duty themes that run through this story, weaving together with the writings of Hobbes, and running through parshat Bechukkotai: Legal authority and governmental power. Reward and punishment. Repentance and forgiveness.

Thomas Hobbes burst onto the European intellectual and philosophical scene in the 17th century with ideas that astounded and amazed, appalled and outraged the intelligentsia of Europe. While he garnered few devoted followers, and cultivated a good deal of antipathy, he did establish Social Contract Theory and founded modern political philosophy and political science. Hobbes was a rationalist to the core. He believed that humans, like everything else in the universe, are matter in motion ineluctably obeying physical laws. Our nature is entailed entirely in our physicality; Hobbes did not believe in incorporeal or metaphysical entities such as an immaterial soul. Every event has a mechanistic cause; the universe operates by cause and effect. The chain of cause and effect includes human behavior. Drilling that idea down to the core, the conclusion is that we have no free will and the universe is deterministic. We humans are, in essence, biological machines that operate by seeking pleasure and avoiding pain; we cannot do otherwise. (In this sense, Hobbes presaged Freud’s pleasure principle.) The greatest human motivators, Hobbes wrote, are fear and hope. It’s easy to envision Hobbes’ commentary on Mike Anderson’s story: the fear of incarceration, and knowing he could be picked up at any moment, inspired (read: caused) Anderson to change the course of his life.

In his most famous work, Leviathan, Thomas Hobbes explicated his theory of the Social Contract, whereby individuals consent either explicitly or tacitly to surrender a portion of their freedoms to an absolute authority—a ruler or sovereign—in exchange for protection of rights the ruler can guarantee. Without such a ruler, the world would descend into “the war of all against all” in which “every man is Enemy to every man” and where “the life of man [is] solitary, poore, nasty, brutish and short.” Criminal behavior, including armed robbery, is an aspect of “the war of all against all” which government prevents by establishing laws and imposing punishments.

For Hobbes, much of Torah reads like a Social Contract. God is the absolute ruler who imposes laws of every type on Israel and, in exchange, promises them protection from their enemies and rain in its season—as well as all the blessings that flow from security and abundance. Legal authority based on divine power; reward and punishment.

Parshat Bechukkotai (and in particular Leviticus 26) illuminates the biblical theology of reward and punishment. The parashah opens:

If you follow My laws and faithfully observe My commandments, I will grant you rains in their season, so that the earth shall yield its produce and the trees of the field their fruit. Your threshing shall overtake the vintage, and your vintage shall overtake the sowing; you shall eat your fill of bread and dwell securely in your land. (Leviticus 26:3-5)

What is more, if you obey God, God’s local address will be in your zipcode. (Recall that Anderson said: "If you do the right thing, good things will happen in your life…”)

If you do not obey God, Bechukkotai continues, your lot will be misery, pestilence, and famine, and you will be overrun by wild beasts and enemies. Torah doesn’t shy away from graphic images, such as this:

If… you disobey Me and remain hostile to Me, I will act against you in wrathful hostility; I, for My part, will discipline you sevenfold for your sins. You shall eat the flesh of your sons and the flesh of your daughters. I will destroy your cult place and cut down your incense stands, and I will heap your carcasses upon your lifeless fetishes. I will spurn you. (Leviticus 26:27-30)

Hobbes argues that the Bible mirrors, or expresses, his Social Contract Theory, and sets out to prove his thesis. But does it? Let’s consider Hobbes’ argument.

In Leviathan 3:40, he argues that Abraham obliged himself and his descendants to God. He goes to great length to point out that God spoke only to Abraham yet all those after him were fully obligated to accept Abraham as “their father and lord and civil sovereign.” This demonstrates for Hobbes that, lacking an individual supernatural revelation, one “ought to obey the laws of their own sovereign in the external acts and profession of religion.” As I mentioned, Hobbes championed the absolute power of rulers.

Continuing with the biblical model, Hobbes notes:

The same covenant was renewed with Isaac, and afterwards with Jacob, but afterwards no more till the Israelites were freed from the Egyptians and arrived at the foot of Mount Sinai: and then it was renewed by Moses… in such manner as they became from that time forward the peculiar kingdom of God, whose lieutenant was Moses for his own time: and the succession to that office was settled upon Aaron and his heirs after him to be to God a sacerdotal kingdom forever. (Leviathan 3:40)

Initially, Moses lacked authority by reason of succession: he did not inherit it from Abraham. On what, then, did Moses’ authority stand?

His authority therefore, as the authority of all other princes, must be grounded on the consent of the people and their promise to obey him. And so it was: for "the people when they saw the thunderings, and the lightnings, and the noise of the trumpet, and the mountain smoking, removed and stood afar off. And they said unto Moses, Speak thou with us, and we will hear, but let not God speak with us lest we die."

There you have several of his key points: the consent of the governed, absolute authority, and governance through fear.

At Sinai, however, God spoke directly and solely to Moses, establishing his supreme authority to interpret God’s word and will. Korach and his minions challenge that authority, and God responds resoundingly. The earth swallows them up and the matter is settled.

In Hobbes’ mind, the Torah establishes the wisdom and legitimacy of the Social Contract in which absolute sovereigns make laws and mete out punishment to citizens. If autocrat rulers operate by the consent of the governed, one must wonder about revolutions across the expanse of the globe and throughout the centuries, including in the realm of religion.

Thomas Hobbes’ interpretation is proof positive that you can read whatever you want into the Bible. The claim of the nihilist philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche fits here: “There are no facts—only interpretations.”

There are those today who would see Torah, the Bible, and all sacred religious writings as a social contract commanded and enforced by God, who rewards and punishes, if not in this world then in the next. This perspective has always bothered me for many reasons. It reduces religion to a harsh legal code with an even harsher enforcer. It suggests, without intending to, that perhaps Hobbes’ rejection of free will in favor of a deterministic universe, is consistent with the world religion too often creates: threat of punishment brings about “spiritual change.”

I would prefer to take Mike Anderson at his word: he recognized how poor his choices had been and chose to change the focus of his life, “turned [his] life over to God” (as he put it) for strength, inspiration, and reinforcement, not as a slave cowering at the thought of divine punishment. I applaud Judge Brown’s decision: Anderson is a changed man—because he chose to change and did the work of teshuvah (repentance) necessary to change. Kol hakavod (all honor to him).

Reducing religion to a legal code by which a sovereign maintains order—which far too often happens in the Jewish world under the guise of halakhah—diminishes its spiritual potency. I prefer to view Judaism as cornucopia of sacred possibilities or, if you prefer, a toolbox for realizing our human potential, connecting with the divine, and meeting in community.

© Rabbi Amy Scheinerman

No comments:

Post a Comment